A 10 catchment comparison of how multi-year climate controls catchment recharge, storage and streamflow using over a century of data in Northern Utah

–Meg Wolf, Logan Jamison, D.Kip Solomon, Court Strong, Paul D. Brooks

[bs_collapse id=”collapse_bb86-afd7″]

[bs_citem title=”Bio” id=”citem_e610-6c22″ parent=”collapse_bb86-afd7″]

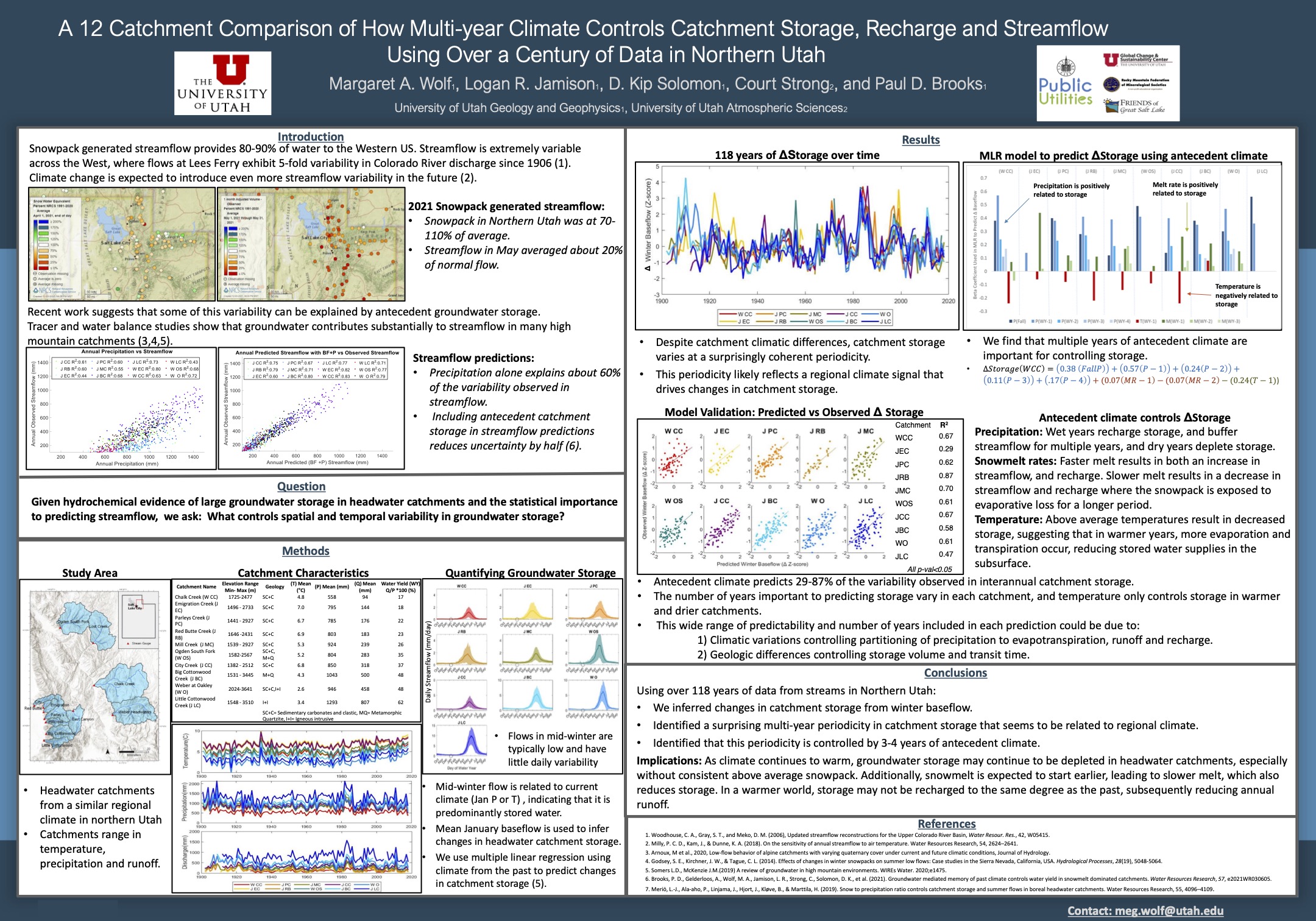

I am currently a PhD candidate working with Dr. Paul Brooks. My work focuses on how water supply in the west is related to current and previous climatic conditions, and how climate change may impact water supply from snowpack generated streamflow in the future. My findings suggest that in snowpack dominated headwater streams that groundwater storage controls a large portion of annual runoff, and that headwater catchment storage is not stationary from year to year. Variability associated with changes in catchment storage are related to regional climate signals from up to 3-4 years in the past.[/bs_citem]

[bs_citem title=”Abstract” id=”citem_eca8-96a7″ parent=”collapse_bb86-afd7″]

Snowmelt-generated runoff, is typically characterized by high annual variability. Predicting this variability is essential to water managers. Recent studies suggest that including antecedent groundwater storage in water yield (WY) predictions reduced uncertainty (from ~40%-~20%) in 10 Northern Utah catchments. We therefore ask 2 questions, how does winter baseflow vary over time, what controls this variability? Using over a century of discharge and climate data, we find that winter baseflow follows a synchronous decadal periodicity across all catchments, suggesting a multi-year climate signal. We used multiple linear regression to predict changes in winter baseflow using previous climate. We find that the previous 4 years of precipitation, 1 year of temperature, and up to 3 years of melt rate control winter baseflow. This study expands on the standard one-year water balance and suggests that multi-year climate and its control on storage can either buffer or exacerbate future streamflow surpluses or deficits.

[/bs_citem]

[bs_citem title=”Video” id=”citem_780c-0f71″ parent=”collapse_bb86-afd7″]

Mountain snowmelt provides a large part of the western US’s water supply. This snowmelt provides water to streams in 2 major ways 1) directly to streamflow during snowmelt (fast flow), and 2) by refilling groundwater storage reservoirs in the subsurface of the mountain catchments, which then gets released to streamflow later in the year (slow flow). We find that each year streamflow can change dramatically, sometimes we have a big water year, and other years we have drastically low water years, like in 2021. These high or low years can occur, even if we have a normal snow year. We find that some of these year-to-year changes in streamflow are controlled by how full, or how empty the subsurface storage is in a watershed, these storage reserves seem to be re-filled at a 3–4-year timescale, meaning that if we are trying to consider how much runoff the stream will receive in 2022, it is important to not only consider how much snow we received in 2022 but also to consider the climate from the previous years.

[/bs_citem]

[/bs_collapse]